On May 10, 2022, the conference ‘Enjoying Life Approach on location’ took place in Arnhem (in the Netherlands), as a completion of the eponymous project. Marieke Braks, director of long-term care at VGZ and host of the conference, said that the first steps in the project started with a cup of coffee and that she is proud of what has been achieved since then, with all those involved. Tineke Abma, director of Leyden Academy and professor of Elderly Participation at the Leiden University Medical Center, then discussed good care and care ethics: 1) it is very personal, 2) it is a reciprocity, in coordination with residents and relatives, and 3) it starts with attention and insight into wishes and desires.

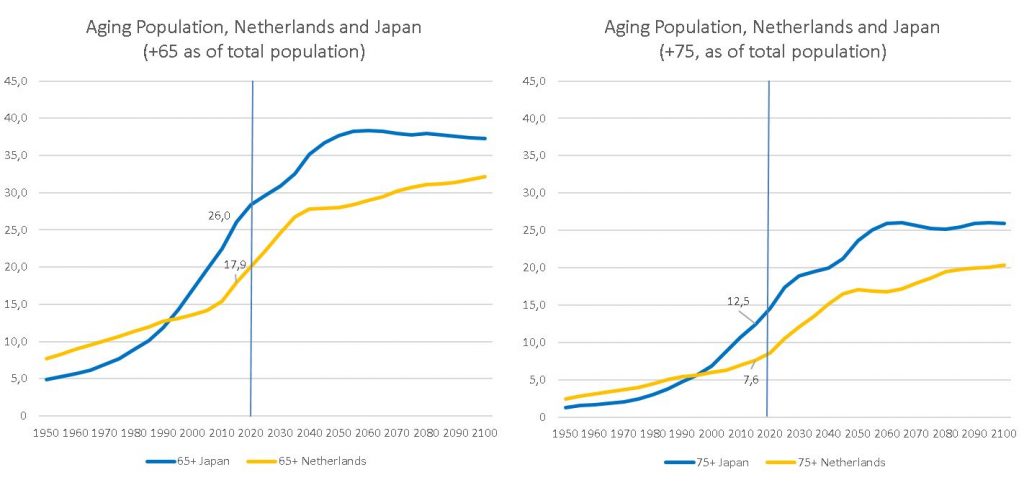

In addition to ‘attention’, according to Theo van Uum, director of Long-term Care at the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, ‘trust’ is also a key word. He finds the Enjoying Life Approach an inspiration that puts the elderly in control, and he believes the scalability of the approach is promising. However he indicated, we must be aware of, on the one hand, the growing number of people with dementia (from 300,000 to approximately 500,000 in 2040 in the Netherlands) and, on the other hand, the shortage on the labour market.

After the plenary part, the participants discussed in various workshops subjects related to person-oriented care.

“Two years ago I mainly focused on carrying out the care tasks. Everything has changed since we focus on person-oriented care. That has done a lot to my job satisfaction. Even though we have a route, it no longer feels like a list I have to work through. I just enjoy doing it now.” – Employee

Book about person-oriented care

As a result of the project, a book (in the Dutch language) has been made, packed with striking photos, experiences, stories and practical tips. Tineke indicated that she is pleased with the fact that the project has been anchored in practice. She handed over the first copies to elderly care employees Wendy van der Ven and Gwendolyn Graven and asked them for a reflection on their experiences with the Enjoying Life Approach. Wendy: “You ‘see’ each other and share with each other. You need each other and everyone is valuable; residents, relatives, and employees.” Gwendolyn: “It is a process, it is never finished. You have to get to know each other and give each other space, even when you face dilemmas.”

“Last summer it was my birthday. The nurses bought a present, which they let my mother give to me. I thought that was so wonderful. My mother really feels at home at the care facility. The care employees and the residents have really become family to her. I’m not the most important person to her anymore. And I don’t mind at all.” – Relative

A film with love

What we can’t express in words, needs to be experienced. That’s why we made a short film ‘With love’ (also in Dutch), which premiered at the conference. ‘With love’ follows Piet and Annemarie and her Bernard, and shows the person behind the resident: attention gives recognition. In the film you can see that employees provided a hook-up bed, so that Bernard can stay with his wife every now and then. And Piet gets emotional by a Doodle board that a care worker made for him after a pleasant conversation and a dance.

“I think it’s important that have good contact with the nursing staff. That you can rely on them and that they keep to their promise.” – Resident

Action research

Implementing the Enjoying Life Approach in practice is not easy: there are sometimes (practical) objections between dream and deed. From 2019 to 2021, the action research focused on the training and coaching of employees as well as the redesign of the electronic client file, work processes and accountability frameworks at two elderly care organisations.

The research was supervised by Leyden Academy and supported by the care offices of Menzis and VGZ, the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, the Dutch Healthcare Authority, the Health Care and Youth Inspectorate, and the KIK-V program of the National Health Care Institute.

“We had a lady who absolutely did not want to be showered. Every time it was a fight. The family could hardly believe it. The son was invited to attend once. It turned out that Mrs. did not want a stranger to help her in the shower, but that she enjoyed it when her children did it. From then on the children helped her shower. For them it was a nice way to make contact, for the staff it was a relief.” – Manager

Mindset change

Mindset change

On November 11, 2021, our colleague

On November 11, 2021, our colleague