The International Longevity Centre (ILC) Global Alliance is a multinational consortium with a mission to help societies to address longevity and population ageing in positive and productive ways. Leyden Academy represents The Netherlands in this global network.

The ILC Global Alliance is currently working on a systematic overview of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in 16 countries, on issues like mortality, policy, societal debate, ageism, social isolation, and abuse. From the perspective of the Netherlands, Professor Tineke Abma and Dr. Elena Bendien have submitted the article ‘Silver lives matter’. It provides context on the Dutch healthcare system, an overview of the course of the pandemic and the response of the Dutch government, and highlights various debates and dilemmas regarding older people that manifested as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and restrictive measures. In the concluding remarks, the authors argue that the crisis exposed shortcomings in the Dutch systems for healthcare and care for the elderly.

Please read the article ‘Silver lives matter’ below. A link to the earlier ILC Global Alliance position statement regarding COVID-19 and the rights of older persons can be found here.

*****

SILVER LIVES MATTER

How intelligent was the Dutch ‘intelligent lockdown’ for the older Dutch people?

Introduction

The retrospective analysis of the Dutch National Institute for Public Health and Environment (further RIVM) published in June 2020, shows that before the first confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis in the Netherlands on February 27 was made, 154 people had already been infected, with the first complaints traceable as far back as January 1.[1]

Just before the first confirmed diagnosis, the annual Carnival was celebrated in the Southern province of North-Brabant.

During the second COVID-19 related press conference on March 9, the Dutch Prime Minister announced that as of that moment, shaking hands as a form of greeting would be temporarily forbidden. And at the end of that conference he shook hands with the director of RIVM…

The Netherlands anno 2020 is a knowledge society. It has one of the most developed healthcare systems in the world, which is driven by efficiency, market forces, flexible labour and highly specialised care. SMART criteria for setting objectives and a LEAN type of organisation are principles that define most of the Dutch healthcare landscape today.

In 2015 an important transition took place in care for the elderly. Living and care facilities for older people with minor healthcare needs were closed during the following years, due to the high costs which, according to the national statistics office (CBS), were no longer sustainable. The older people were expected to live at home as long as possible. Today, an indication for a care or nursing home is reserved for older people with severe somatic or psychogeriatric problems only. As a result the entire population living in the elderly care facilities today is very frail.

Dutch healthcare and care for the elderly are recurrent themes in the national public debates. The main topics of these debates are the lack of care personnel on the labour market due to flexible contracts, low pay for the personnel, (over)regulation and the protocolisation of care work, which is prioritised over person-centred care, equal access to care for the various population groups etc. This is the context within which the first COVID-19 diagnosis was made public in February 2020. In the meantime, all 2,351[2] Dutch nursing homes accommodating more than 120,000 older inhabitants remained open for visitors, carrying on business as usual, including the homes in the province of North-Brabant.

Statistics

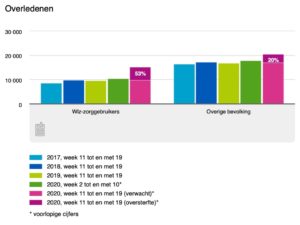

The first confirmed cases of COVID-19 were quickly followed by the first deaths (the first one on March 6). The mortality rate increased exponentially and within several weeks CBS was already speaking about excess mortality. During the first nine weeks of the Corona-pandemics in the Netherlands (weeks 11-19, i.e. March 9 – May 10), excess mortality was estimated at ca. 9,000 cases. This is 32% higher than the expected number of deaths during the same period of time before the pandemics. During the first two weeks, excess mortality increased with 10%, and in the fifth and sixth weeks it was already circa 55%.

Excess mortality was especially high among men between 75 and 90 years old, who lived in care or nursing homes and/or had a migration background. Their mortality rate was 42% higher than could normally be expected (compared with the data from 2017-2019).

The mortality rate among the users of long-term care (WLZ) was 53% higher than normal.[3]

WLZ-zorggebruikers = users of long-term care

Overige bevolking = rest of the population

The most dramatic development took place during the weeks 14 and 15 of 2020 when, according to the CBS figures, the mortality rate in nursing homes and other long-term care facilities had doubled. In the first 10 weeks of 2020 approx. 752 people died weekly in the elderly care institutions. During week 14 the number increased to 1,396 and during week 15 to 1,589 deaths.[4] Around the same time, based on the analysis of electronic dossiers of the clients living in care and nursing homes, approx. 5,300 older inhabitants turned out to be infected by COVID-19. From week 16 on, due to the protective measures introduced at a national level, the mortality rate in the sector for elderly care showed a slow but stable decrease, resulting during week 20 in a level, comparable with the situation before the pandemic.[5]

According to the epidemiological overview of RIVM[6] published on June 5, the Netherlands lost 6,005 people to COVID-19. More than 94% of them were 65 years and older. Approx. 62% of all cases relate to people who were 80 years and older. Approx. 46% of all deaths were inhabitants of care or nursing homes for older people.[7]

Governmental response

The Dutch government reacted to the pandemics by introducing a so called ‘intelligent lockdown’. That decision was made by the Ministerial Crisis Management Committee (the Prime Minister and a number of cabinet ministers) based on advice of the Outbreak Management Team (the director of RIVM, academic researchers and specialists in infectious diseases and virology).[8] The choice for an intelligent lockdown reflects the cultural and political values of the Dutch society, i.e. autonomy, self-regulation, active citizenship and personal responsibility. Intelligent lockdown is a relatively mild protective measure, which regulates public life where this is strictly necessary. E.g. the Dutch lockdown meant temporarily closing all recreational areas and facilities, restaurants, hotels and services where physical contact is involved. An urgent appeal was repeatedly made to all citizens to stay at home in cases when being outside or travelling was not absolutely necessary.

The communication about the spreading of COVID-19 was slow and caused a lot of confusion at the start. At the same time, the communication was frequent and quite transparent. From March 6 till the end of June 2020 the Prime Minister held 36 press-conferences directly related to the pandemic.[9] The governmental approach to the situation invoked serious criticism, especially regarding issues such as group immunity, low testing capacity, the lack of protective equipment and a very late response to the situation in the care sector for the elderly.

In the middle of March, it became necessary to close several care and nursing facilities for external visits in the Southern provinces of North-Brabant and Limburg, due to the increasing number of infected inhabitants.[10]

On March 19 the government, supported by the House of Representatives, took the decision to cancel all personal visits to all care and nursing homes in the Netherlands.[11] In retrospective it was already too late; the virus was spreading quickly among the frailest group of the Dutch population, including their professional staff, who were working without protective equipment there.

In April, when the dramatic numbers of deaths in the care and nursing homes became public, the director of the Catholic and Protestant unions for older people Manon Vanderkaa reacted to the situation by saying: ‘An invisible disaster is going in the nursing homes.’[12] She, as well as other research, clinical and public institutes like ActiZ (the branch organisation of care professionals working with older people, people with chronic diseases and youth), ANBO (the Dutch Union for Senior Citizens) and Verenso (the Dutch Association of Elderly Care Physicians) pleaded for immediate provision of protective equipment for the staff working in care and nursing homes.

Today a vast variety of COVID-19 related resources is available on the websites of various governmental organisations,[13][14][15] including the patients’ organisations.[16]

Front line fighters and a country of volunteers

On March 17 at 8PM the Dutch people applauded from the windows, balconies and roofs of their houses, the care professionals, as a token of appreciation for their devotion and professionalism which they had shown from the very beginning of the pandemics. Retired care professionals and medical students massively applied for voluntary work in various medical facilities.[17] Because of precautionary measures, the majority of the older people stayed at home for weeks. Many initiatives were born in order to help them to survive during this time of uncertainty.[18] The website ‘Coronahelpers’[19] is a good example of how people with questions and those who offered help could be brought in contact with each other.

The work of the IC-nurses and doctors was in the centre of political and public attention from the very beginning of the pandemics. The costs cuts of the previous years in the healthcare sector reflected on the personnel that was available. The required increase in the total number of IC-beds from 1,150 before the crisis, to 1,700 IC-beds during the pandemics, demanded extra capacity from the already overworked hospital nurses and doctors.[20] The fact that the care and nursing home professionals were not only overworked, just like their hospital colleagues, but had to continue working without protective equipment, with their infected clients, resulted in quickly spreading infection among nursing home personnel. Many of them are self-employed, which makes their economic position even more vulnerable in times of crisis.[21] One Dutch study on the prevalence of COVID-19 among the professionals in one of the nursing homes showed 10% of staff having various types of symptoms, a direct result of infection by the virus (Luttje et al., 2020).[22] The care personnel for the elderly never abandoned their duties. However, working in difficult circumstances without fitting protection has led to negative emotions, fear and a feeling of being left in the lurch. In the middle of April, it was announced that at least 8,000 care professionals working in various branches had been infected with COVID-19.[23]

At the end of June 2020, the Minister of Health, Welfare and Sport announced a benefit payment, the so-called corona-bonus, of 1,000 euro for the healthcare professionals.[24] The announcement was followed by a bitter discussion of who’s and how’s in regard to the actual payment. In spite of the good intentions, the actual carrying out of the decision has not been sufficiently thought through. Today the healthcare professionals say aloud: enough applause, it is time for action!

Public debates involving older people in times of Corona

Times of crisis sharpen our focus on issues that actually matter. The pandemic gave a new boost to the debates on gender inequality, equal access to healthcare for all population groups, uncertainty on the labour market for people without a permanent contract or for the self-employed and many other issues. In this short overview we concentrate on several topics related to older people:

(i) Economic versus personal suffering (isolation and loneliness);

(ii) Policies and lessons;

(iii) IC-protocol phase 3: non-medical reasoning for allotment of an IC-bed;

(iv) ‘Dry wood’ and self-determination, or explicit ageism versus internalised ageism.

(i) Economic versus personal suffering (isolation and loneliness)

Further into the pandemics the question about the priorities and choices of the Dutch government during the crisis became more urgent, i.e. to limit economic harm or to prioritise measures relieving personal suffering? Closing businesses had both humanitarian and economic reasons. Firstly, the lockdown was meant to prevent the spreading of the virus and to protect the most vulnerable groups. Secondly, it had also a macro-economic incentive, because uncontrollable spreading of the virus meant an exponential increase in costs and an eventual collapse of the entire healthcare system.

Already on March 17, the government came up with the package of measures in order to support the Dutch economy, including small and medium businesses.[25] ‘The measures’ to relieve the growing loneliness and isolation of the nursing home inhabitants were never discussed at a governmental level.

The debate that is being carried out since then, addresses complex issues. In retrospective some of the choices that have been made, are more susceptible to criticism than others. When the decision about closing businesses had been taken, everybody understood the personal and macro economical risks involved: no clients – no salaries, no orders – no income. When the decision to close the care and nursing homes for visits had been taken, only those directly involved felt the full measure of the consequences. Somebody in frail health can die during a ‘no visitors’-period, not from the virus, but because she or he becomes very lonely or because it is time to die. Dying alone is inhuman; also it can be a traumatic experience for family and friends who were not able to say goodbye properly. On the other hand, closing elderly care facilities for visits, created some space for the care personnel who were exhausted at that point and often also frightened of being infected, of being carriers of the virus and therefore unknowingly infect their families, or of being unable to help their older clients.

In April-May 2020 the Dutch Trimbos-institute for mental health issues investigated whether the inhabitants of nursing homes felt socially isolated during the COVID-19 crisis. The first part of the research was carried out with care professionals working in nursing homes (N=533) and with family members (N=913) of people living in nursing homes. Most of the data came from the two Dutch provinces North-Brabant and Limburg, that had been most seriously afflicted by the virus.[26] Some of the results are:

a. There is a consensus about the necessity to cancel physical visits;

b. Professionals and family members confirm that the feeling of loneliness among the older clients has increased since the ban;

c. Quality of life of the older people is estimated to be lower by both the professionals (from 8 to 6) and the family members (from 7 to 5 on a 10-point scale);

d. Family members find that the general health of their older relative has declined during the pandemics; 44% of professionals share this opinion, 65% of professionals estimate the health of their clients as good or very good;

e. Contact with the older inhabitants is facilitated by various means:

Beeldbellen = video call

Raamcontact = window contact

Buitenruimte = outside

Zorgmedewerkers = care professionals

Familieleden = family members

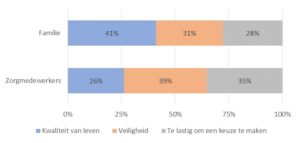

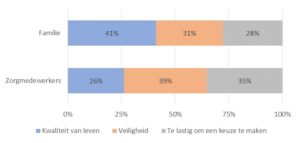

f. Probably the most important finding regards the question what professionals and family members found to be most important for the older clients: quality of life (‘kwaliteit van leven’) or safety (‘veiligheid’) (the grey area stands for ‘difficult to choose’:

The answers demonstrate one of the complex dilemmas in the care for the elderly during COVID-19: whose wellbeing comes first, the client’s or the professional’s. There are obviously no easy answers here.

(ii) Policies and lessons

In his interview, Professor of Geriatrics Marcel Olde Rikkert (May 2020)[27] critically but constructively evaluated the governmental policies during the pandemics in relation to the health and wellbeing of older people. Several of his points are relevant for this overview:

- The pandemic policies were introduced top-down, the IC-specialists and virologists were mainly advisors of the government, the opinions of other professionals were hardly taken into consideration.

- A lot is known already about ageing processes, but this knowledge has been used sub-optimally during pandemics. E.g. for a long time, fever was seen as an important symptom for COVID-19. However, it is a well-known fact that the normal body temperature of an old person may be up to two degrees lower than that of a young person. An older person with a body temperature of 37 degrees therefore must be tested for COVID-19, which has not been done. As a result, many older people were diagnosed too late, and those working with them were not protected.

- The decision to close care and nursing homes to visits from outsiders was understandable, but required fine-tuning, which has not been done.

- Experience from abroad, e.g. Italy, has not been taken into consideration. The fact that nursing homes could become epicentres, spreading the virus, was known already, but precautionary measures were taken in the Netherlands only after the spreading had already started.

- When it became clear that the Netherlands had to deal with excess mortality, especially among the older population, nothing was done about palliative care, including the possibility to visit dying people in order to say goodbye. ‘Besides quality of life you must look at quality of dying’.

- A large-scale research and a proper dialogue between all parties involved, is necessary to be able to live through the period, that can be better called a time for dialogue than a crisis-time.

(iii) IC-protocol phase 3: non-medical reasoning for allotment of an IC-bed

The underlying question for this debate is the allotment of an IC-place in case of shortage of IC-beds: who will be given priority?

In the beginning of April there were circa 1,400 patients admitted to the IC departments throughout the Netherlands. Each day there were approximately 100 new patients who required an IC-bed. The hospitals in the Netherlands could provide the necessary care to a maximum of 1,900 IC-patients at that point. The Netherlands, given the same rate of incoming patients, had five more days before it would reach its maximum IC-capacity.[28] In that case the doctors had to decide who would be given a priority.

In June 2020 The Royal Medical Association, together with the Federation of Medical Specialists, published the ‘Triage protocol on the basis of non-medical considerations for IC admission during phase 3 of the COVID-19 pandemics.’[29] This is a document that is based on clinical as well as ethical reasoning. Phase 3 means that coordination of a pandemic cannot be carried out any longer at the provincial level and that there is an absolute shortage in capacity, especially in IC- capacity. During the first two steps of phase 3 medical specialists take decisions on medical grounds. Step three addresses the situation where decision-making on medical grounds is not possible anymore. These are several recommendations made for step three, that are relevant for this overview:

- Patients whose stay in the IC-department is estimated to be shorter than that of other patients may be prioritised;

- Care professionals who due to their professional performance had multiple contacts with COVID-19 patients and/ or who, due to the shortage of protective equipment were exposed to the virus, may be prioritised;

- Younger patients have an advantage in relation to older patients, if other factors have not led to the decision (generations are defined as 0-20; 20-40; 40-60; 60-80; 80+). See ‘fair innings’ argument.[30][31]

The choice on the basis of age ignited a new round of public debate about ethics, justice and generational solidarity. In anticipation of the second wave of pandemics the debate is still ongoing. The point about generational choice is explicit and is generating a lot of discussion, while the point about the duration of stay in IC seems to be generally accepted. Yet, also that recommendation implicitly suggests the age-differentiation: a younger patient in good health will very probably recover quicker than an older person.

(iv) ‘Dry wood’ and self-determination, or explicit ageism versus internalised ageism

The Netherlands is not a stranger to ageism and populistic discussions in the times of crisis. At the end of March one of the radio journalists M. Zwagerman[32] came up with a not very original idea about 80+ers who, according to her, generate circa 20% of the healthcare costs, because ‘death has been cancelled’ in the Netherlands. At least two aspects of such prophets in times of uncertainty are problematic. Firstly, such formulations aim to drive a wedge between generations exactly at the moment when solidarity seems to be the best way to go forward. Another aspect is the explicit ageist terminology that cannot be excused either by urgency of the message or by ‘intention to provoke and stimulate a debate’. The older people are called ‘sadly looking grave-diggers’, the virus does its work ‘honestly’ and on top of all that ‘the scythe cuts through the dry wood’. The response to the ‘provocation’ was strong and predominantly critical. Yet, there were also some supporters on Twitter and other social media.

This example is just a tip of the iceberg if we want to take ageism seriously. Zwagerman’s open ageism is easy to criticise, because, while offending older people it is directed at self-promotion. The internalised ageism that the entire society is not aware of, is a much bigger problem. That is why the critical reading of the IC-beds protocol that has been presented earlier is so important.

During the past few months many older Dutch people came to the following conclusion: it is better to stay at home and die in your own bed than to die in a coma in an IC-bed.

The issues of self-determination and autonomy are very important topics in the Dutch public debate. COVID-19 made this topic even more acute.[33] There is however still insufficient transparency in the way the wishes of older people are heard and taken into account.[34] An older person who does not want to be treated any more, can make this decision based on his/her deep conviction that extended treatment will mean extra suffering and additionally entails wasting resources that could be used otherwise. But the same decision can be also made due to an internalised idea that the society does not want or need you anymore, that it is egoistic to prolong your life and that it is your duty to die. Only a thorough critical analysis can help us to separate self-determination from internalised ageism.

Concluding remarks

The events of the last three months have changed our way of looking at ageing and at our future. While we are writing this overview, the Netherlands has eased the lockdown. The visits to (most) care and nursing homes has been carefully resumed for some time already. The homes that were first unwilling to allow visitors were threatened with lawsuits on grounds of violation of human rights.[35][36] At the moment we do not have any factual information about the lawsuits in relation to COVID-19.

During the lockdown there was a lot of attention to domestic violence in the Netherlands. Our expectations were similar to those of the Canadian colleagues. In June however the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport announced that there was no increase in reports on domestic violence during the crisis-period in the Netherlands.[37] The interpretation of the available data must be still carried out.

The crisis exposed shortcomings in the Dutch systems for healthcare and care for the elderly. The labour market which is to a large extent based on flexible contracts, undermines the continuity in all economic sectors, including healthcare and care for the elderly. Quality of life is important for older people living in care or nursing homes, as well as for older people living independently. The COVID-19 measures negatively influenced the lives of many fragile older people.

The Netherlands moves today in the direction of the 1,5 meter-society. What this will mean to the older people remains unclear. The entire process of decision-making during the past few months demonstrated that active participation of older people in our society is far from true. The decisions have been made about them, not with them.[38]

The crisis also brings to light the best in people.

In spite of overwork, lack of protective equipment and personal risks, accompanied by moral dilemmas, the healthcare professionals went on doing their work. A lot of people were inspired by their examples: retired professionals applied for work again, others came to help as volunteers. The cultural sector exploded with creativity: small concerts were organised ‘behind glass’ for clients of nursing homes. I-pads were given as presents to care and nursing homes, in order to allow older people to make video-calls to their families. Small businesses within the communities came up with ideas to deliver fresh meals to community-dwelling older people.

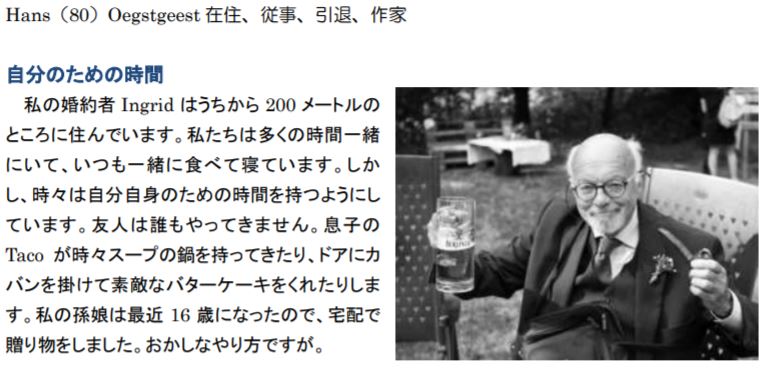

The Dutch organisation for health research and care innovation (ZonMW) made it possible to apply for funding in relation to all aspects of COVID-19 research: clinical, sociological, societal etc. One of the initiatives where Leyden Academy on Vitality and Ageing has been involved from the very beginning together with the GetOud foundation, is the website ‘Wij & Corona’ (‘We and Corona’). The website does what the policies often do not do, i.e. it gives voice to older people themselves. On the website the reader can find dozens wonderful stories told by the older people themselves, about their ideas and experiences in the times of COVID-19.[39]

[1] https://www.rtlnieuws.nl/nieuws/artikel/5140371/corona-cijfers-besmettingen-uitbraak-nederland-eerste-officiele

[2] https://www.zorgkaartnederland.nl/verpleeghuis-en-verzorgingshuis

[3] https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/nieuws/2020/22/sterfte-in-coronatijd

[4] https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/nieuws/2020/18/sterfte-in-verpleeg-en-verzorgingshuizen-daalt-vertraagd-verder

[5] https://nos.nl/artikel/2332431-cbs-coronasterfte-in-verpleeghuizen-loopt-verder-terug.html

[6] https://www.rivm.nl/sites/default/files/2020-06/COVID-19_WebSite_rapport_dagelijks20200605_1128.pdf

[7] https://www.rtlnieuws.nl/nieuws/artikel/5144186/corona-doden-sterfgevallen-overleden-verpleeghuis-ouderen

[8] https://www.trouw.nl/politiek/wie-zijn-de-coronabeslissers-in-nederland~ba68f198/

[9] https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/coronavirus-COVID-19/coronavirus-beeld-en-video/videos-persconferenties

[10] https://www.actiz.nl/nieuws/verpleeghuizen-met-besmettingen-sluiten-voor-bezoek

[11] https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/actueel/nieuws/2020/03/19/bezoek-aan-verpleeghuizen-niet-langer-mogelijk-vanwege-corona

[12] https://www.ad.nl/binnenland/sterfte-onder-bewoners-verpleeghuizen-en-instellingen-bijna-verdubbeld~a5c411d2/

[13] https://www.waardigheidentrots.nl/corona/?_ga=2.158024314.1589801308.1592817042-1611282609.1592469165

[14] https://www.verenso.nl/themas-en-projecten/infectieziekten/COVID-19-coronavirus

[15] https://www.rivm.nl/en/novel-coronavirus-COVID-19/risk-groups

[16] https://www.patientenfederatie.nl/zoeken?search=corona

[17] https://www.bnr.nl/nieuws/gezondheid/10406626/2-700-aanmeldingen-voor-corona-hulp-in-noordelijke-ziekenhuizen

[18] https://www.zorgwelzijn.nl/corona-update-heel-nederland-wordt-vrijwilliger/

[19] https://www.coronahelpers.nl

[20] https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2020/05/07/1700-ic-bedden-gaat-niet-lukken-a3999095

[21] https://www.socialevraagstukken.nl/hoe-zzpers-in-de-zorg-in-een-moreel-mijnenveld-terechtkwamen/

[22] https://www.verenso.nl/magazine-april-2020/no-2-april-2020/actueel/COVID-19-onder-medewerkers-in-het-verpleeghuis

[23] https://coronavirusactueel.nl/8000-zorgmedewerkers-besmet-met-coronavirus-dit-is-onze-frontlinie-bescherm-hen/

[24] https://nos.nl/artikel/2338942-werkgevers-in-de-zorg-willen-niet-beslissen-wie-wel-of-niet-1000-euro-krijgt.html

[25] https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/actueel/nieuws/2020/03/17/coronavirus-kabinet-neemt-pakket-nieuwe-maatregelen-voor-banen-en-economie

[26] https://www.trimbos.nl/docs/620f571c-0607-4d49-8a8a-3a0ae69c8c5b.pdf

[27] https://www.parool.nl/nederland/kritiek-op-corona-aanpak-ze-hebben-alleen-doden-en-ic-bedden-geteld~b8de9ac0

[28] https://www.trouw.nl/zorg/kiezen-tussen-jongeren-en-ouderen-op-intensive-care-is-onwaarschijnlijk-scenario~b0179886/

[29] https://www.demedischspecialist.nl/sites/default/files/Draaiboek%20Triage%20op%20basis%20van%20niet-medische%20overwegingen%20IC-opnamettvfase%203_COVID19pandemie.pdf

[30] https://www.ceg.nl/ethische-dossiers/rechtvaardige-selectie-bij-een-pandemie/documenten/signalementen/2012/12/13/rechtvaardige-selectie-bij-een-pandemie

[31] Bognar, G. (2015). Fair innings. Bioethics, 29(4), 251-261.

[32] https://www.bnr.nl/podcast/marianne-zwagerman/10406521/doodgewoon

[33] https://www.trouw.nl/nieuws/de-meeste-mensen-willen-thuis-sterven-maar-dat-gebeurt-niet~b323bad0/

[34] https://www.gelderlander.nl/arnhem/oproep-wilt-u-thuis-sterven-of-in-het-ziekenhuis-tussen-de-maanpakken-in-tijden-van-corona~ad64f702/?referrer=https://www.google.nl/ ; https://www.leydenacademy.nl/?s=Laat+ouderen+meepraten

[35] https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2020/06/24/na-een-ommetje-heeft-cors-vrouw-weer-wat-kleur-a4004015

[36] https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2020/06/24/na-een-ommetje-heeft-cors-vrouw-weer-wat-kleur-a4004015

[37] https://www.huiselijkgeweld.nl/actueel/nieuws/2020/06/24/niet-meer-meldingen-huiselijk-geweld-tijdens-coronacrisis

[38] https://www.scp.nl/publicaties/publicaties/2020/05/18/zicht-op-de-samenleving-in-coronatijd

[39] https://wijencorona.nl ; https://www.leydenacademy.nl/tineke-abma-geef-ouderen-een-stem-in-de-coronamaatregelen/